An example and template for conducting lightweight post-mortem examinations

There are times when heavy post-mortem examinations and reports are the right thing to do. For example, I assume that Google’s post-mortem work after the recent email phishing campaign went pretty deep.

However, most of the time a more lightweight post-mortem examination and report may be quite a bit more appropriate and much less time-consuming.

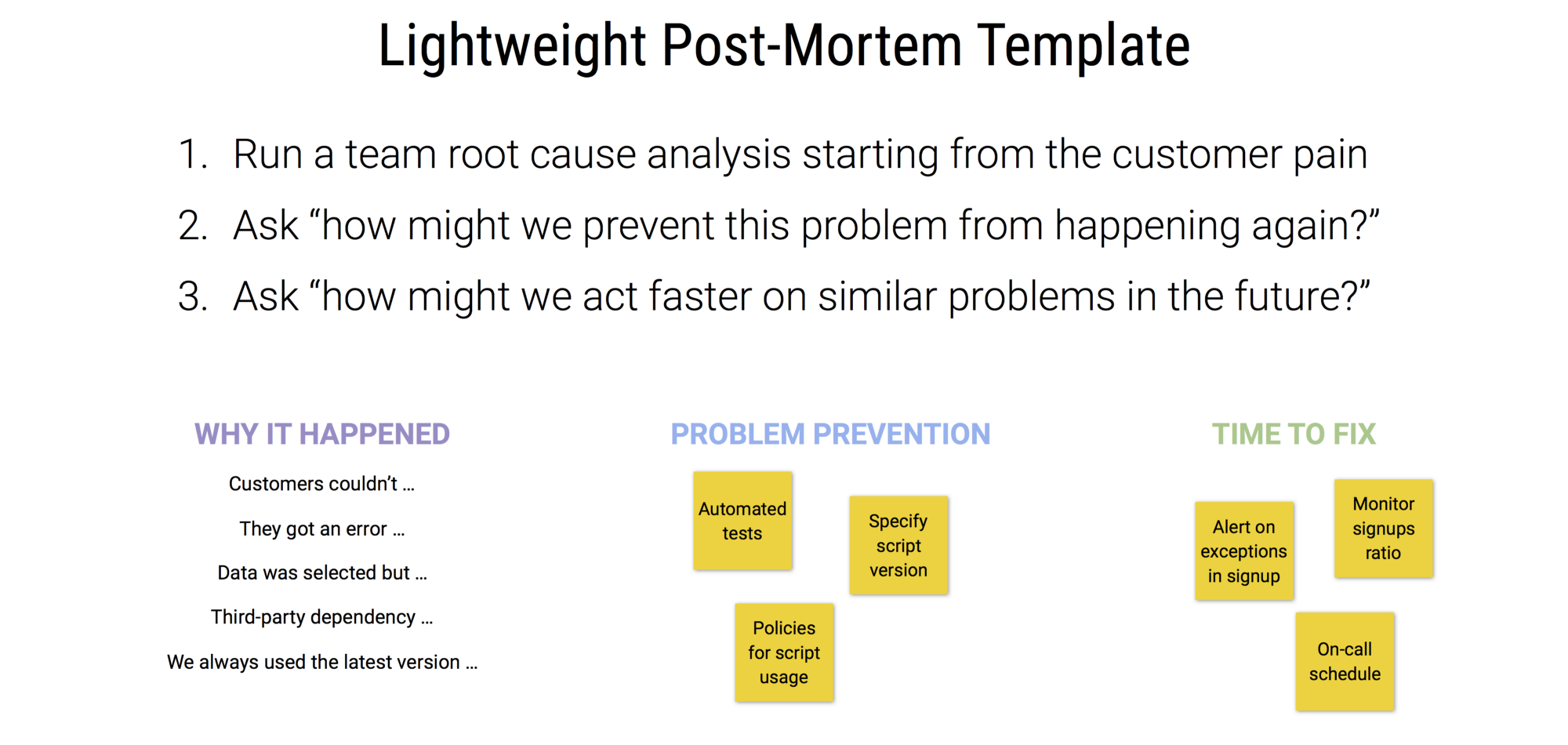

When an incident has occurred, there are three things that should be discussed: 1) why it happened, 2) problem prevention, and 3) time to fix.

Lightweight Post-Mortem Template (downloadable as a PDF, with a bonus, at the end of the article)

The right people #

First, gather the people that has an understanding about the incident and the know-how for improvement. Secondly, facilitate a discussion about how and why the incident happened. Thirdly, decide which people are needed for problem prevention and then who’s needed to improve on time to fix.

It’s not unlikely that problem prevention and time to fix yield different people.

Why it happened #

Although we’ll use root cause analysis to identify and create understanding of the faults or problems that led to the post-mortem, we’re not really looking for ‘root causes’ so much as identifying where improvement would prevent the broadest classes of problems going ahead.

We remind ourselves, before we start, that while someone probably made a mistake at some point, we all somehow built a system that let that mistake happen. This is an opportunity to improve that system — through additions of, or changes in the likes of, processes and policies.

Only after reminding ourselves about no blaming do we start working towards a shared understanding about the incident why’s and how’s by first framing the “bad thing” that happened in terms of customer pain.

To move blame from a person to the system it might be useful to use “hows” instead of “whys”. (e.g. how did this happen, instead of why did this happen.)

After framing the incident, we explore it further by asking why and how the incident happened, until it doesn’t feel productive anymore; for example:

- What? Customers’ found it impossible to sign up for our service.

- Why? They got a validation error saying no territories were selected.

- Why? Territories were visually selected, but not populated into post data.

- Why? A third-party dependency was updated and broke our JavaScript.

- Why? We include the latest version, which was updated with a bug.

You can stop here, or your can continue if you’re comfortable in finding organisational problems you’d like to address, e.g. this might have happened because of lacking Task Relevant Maturity and training.

Now that we have a working understanding of the incident, we can figure how to be alerted faster of similar incidents in the future and come up with procedures to try and avoid it from happening again.

Problem prevention #

Problem prevention is all about finding ways to make sure some problems does not happen again, and it’s fairly easy to do.

First, find a proper level from the root cause analysis to start with.

In the example above, the first two items aren’t useful when it comes to problem prevention, but the other three are.

Then ask “how might we prevent this problem from happening again?”

Our third item, territories were visually selected, but not populated into post data, is something we can prevent in the future through automated tests.

We’re not likely to do anything about the forth item, it’s probably going too far to stop using third-party libraries in our application. However, the fifth point is something we can avoid by always specifying a version to use.

So, by upping our automated tests game and adding policies regarding third-party libraries into our current processes, we can prevent similar problems from occurring again.

Time to fix #

Time to fix focus on reducing the time between when an incident occur to when it’s first fixed. Contrary to problem prevention this usually involve alerts, monitoring and procedures surrounding those, e.g. on-call shifts.

Time to fix start the same way as problem prevention do: find a proper level from the root cause analysis to start with, though it’s likely not the same items as during the problem prevention session.

Then ask “how might we act faster on similar problems in the future?”

With the example above, we could end up with things like: alert the person on-jour if new signups are lower than expected, or prioritise exceptions and unlikely hight ratio of validation errors from signup related flows in the app.

Conclude #

That’s it, you should now have a good-enough root cause analysis, logical actions for preventing similar problems in the future and a plan for what needs to be done to improve upon the time between when an incident occurs and when it’s fixed.

Download the PDF version of the template (direct link, no signup-wall).

Bonus #

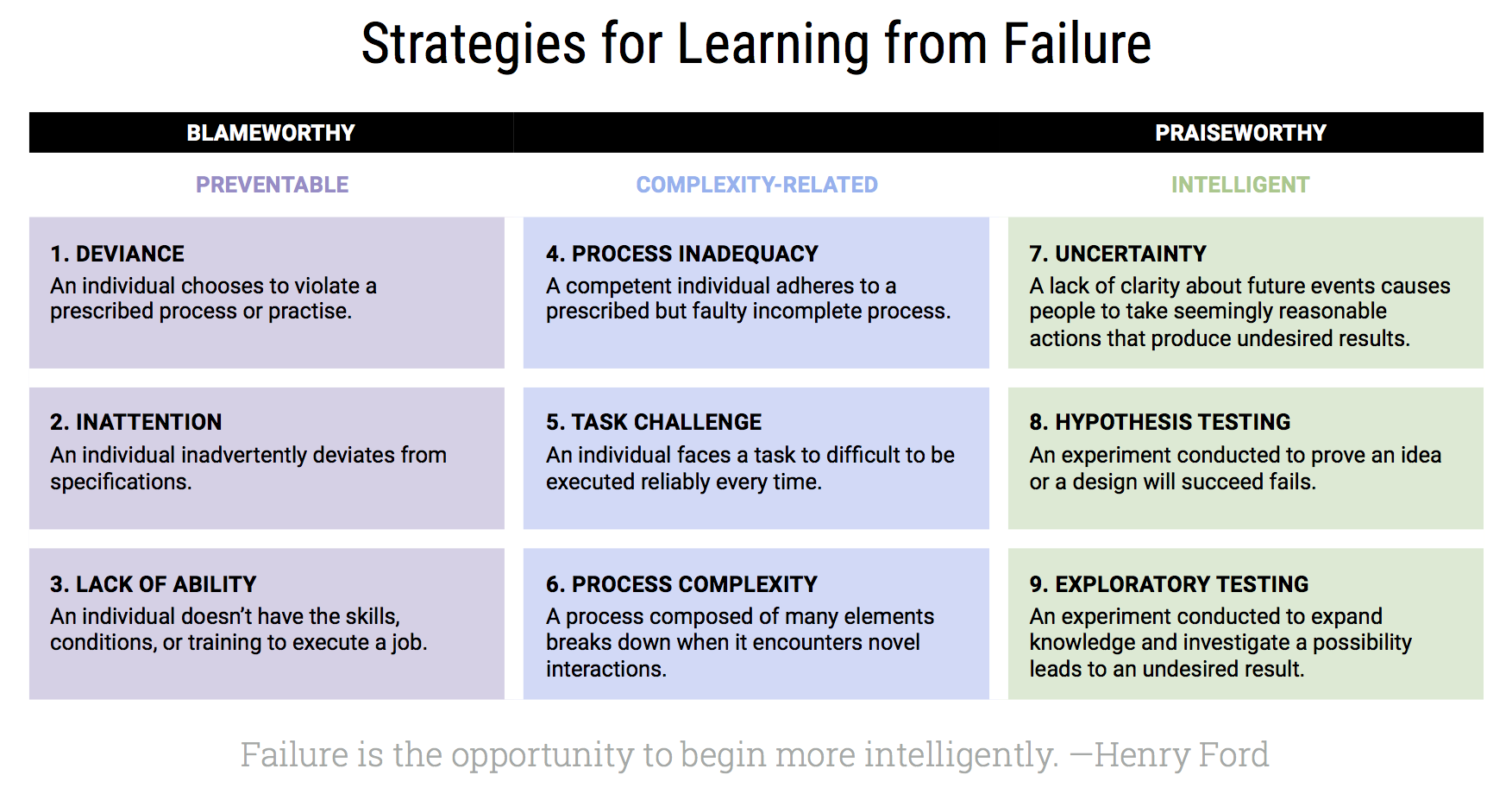

There’s a great article by Harvard Business Review called Strategies for Learning from Failure which talks about the blame game and how not all failures are created equal. It also introduces a a spectrum of reasons for failure which is a useful reference to look at when an incident happens.

You can also download a PDF version if you like (it’s a direct link, no signup-wall). The adapted version is a high resolution remake of an image from the Hyper Island course Leading Teams in the Digital Age (highly recommended btw).